The international project worth over 18 billion euros, in which the employees of the Department of Microelectronics and Information Systems at the Faculty of Electrical, Electronic, Computer and Control Engineering have been involved since 2010, is called the construction of an artificial sun. The analogy is not accidental because, as dr hab. inż. Dariusz Makowski says,

Until now, energy has been generated in nuclear power plants, where the fission reaction in uranium produces large amounts of energy. The world has been trying to shift away from this method because of the risks it poses. Energy from coal is also widely used but also here the awareness of the effects of exploiting this raw material and its limited deposits are the reason why new solutions are being sought. One remedy for the methods of power generation used so far may be a reaction reverse to fission, i.e. fusion, where the light atomic nuclei merge, as happens in the Sun..

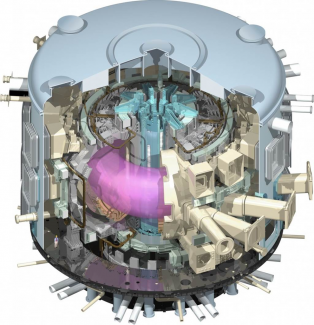

The goal of the ITER project is to build a tokamak, a machine for controlled fusion reactions. Tokamak supplied with deuterium and tritium will produce helium and, above all, huge amounts of energy will be created.

Next to researchers from other countries, such as the European Union, the USA, India, and China, TUL scientists work to recreate the processes taking place in the Sun where nothing alarming happens when energy is generated and where the amount of energy produced is enormous. This process, unlike nuclear reactions, does not produce any radioactive waste.

The central problem is to generate and hold a plasma at a temperature of hundreds of millions degrees Celsius over a long time. Until now, there has been no plasma project in the world that would generate more energy than it has consumed. ITER is the first project in the world to prove that this can actually be done

- dr hab. inż. Dariusz Makowski.

The role of scientists from the team managed by professor Andrzej Napieralski is strategic. They build electronic and IT solutions for plasma control and diagnostics systems. There will be over 70 of them in the entire project. Although from the very beginning, the work on the reactor has been carried out by physicists, at some stage in the project, a need was identified to acquire, process, and analyze tens of thousands of signals in real time, which made it necessary to involve experts in modern electronics and computer science.

In the opinion of dr hab. inż. Dariusz Makowski, developing new methods required to design and build such complex systems is a powerful challenge:

We develop new technologies for designing electronic devices, software, and the process of integrating diagnostic and control systems for the tokamak. The number of organisations involved in the project is so large that it is vital to consolidate the process of design and integration of individual components. The importance of the consistency is clearly exemplified by signal naming or variables that store the measured parameters. If each country or research centre responsible for producing these systems were to name, for example, the temperature in their native language according to their national standards, criteria, and ideas, the process of integrating them would be much more difficult and lengthier. These signals, variables must be the same, the design methods at multiple levels must be standardized so that these individual systems will eventually form one. The same is true for the process of designing and integrating complex, distributed electronic and IT systems.

At Lodz University of Technology, prototype data acquisition and control systems are also being developed. As mgr inż. Piotr Perek explains:

The prototypes are intended to verify and improve the methods of designing electronic and IT systems for the ITER tokamak. At the same time, the demonstration solutions developed by us provide the basis for the development of final diagnostic systems.

This approach is intended to facilitate the design and production of the final solutions to be used in the ITER project, the optimal parameters of which are expected to be achieved by 2035. Right now, the Final Design Review is under way. The next step will be to build diagnostics and conduct the first hydrogen plasma tests - a time horizon of 5 years.

The research is scientific in nature and its aim is not commercial power generation, but rather the development of new technologies for energy acquisition. Further projects are planned for fusion energy production: DEMO and PROTO.